Nederland As I Remember It, 1935-1960

By W. T. Block

Around 1935, my brother, L. Otis Block, and I often walked from the

cemetery in Port Neches to 10th Street in Nederland, and often no more than two cars would

pass us during the entire forty minutes or so that it took for us to walk the two and

one-half miles between those points. The only two paved roads in Nederland in those days

were Twin City Highway and Nederland Avenue (both of which were paved in 1921), east of

the railroad tracks. Nederland Avenue to the west was shelled only to the

"interurban" right-of-way (where Gulf States high lines cross), and beyond the

1500 block, Nederland Ave. consisted of two thin threads of shell going out to Saul

Trahan's dairy (in about the 3000 block), with a sea of bitter weeds with yellow flowers

growing between the threads. In 1938 the county bought the airport property and promptly

paved Memorial Highway with two lanes of concrete. At the same moment, the state also

paved Nederland Ave., also 2-lane, all the way to Twin City Highway.

Around 1935, my brother, L. Otis Block, and I often walked from the

cemetery in Port Neches to 10th Street in Nederland, and often no more than two cars would

pass us during the entire forty minutes or so that it took for us to walk the two and

one-half miles between those points. The only two paved roads in Nederland in those days

were Twin City Highway and Nederland Avenue (both of which were paved in 1921), east of

the railroad tracks. Nederland Avenue to the west was shelled only to the

"interurban" right-of-way (where Gulf States high lines cross), and beyond the

1500 block, Nederland Ave. consisted of two thin threads of shell going out to Saul

Trahan's dairy (in about the 3000 block), with a sea of bitter weeds with yellow flowers

growing between the threads. In 1938 the county bought the airport property and promptly

paved Memorial Highway with two lanes of concrete. At the same moment, the state also

paved Nederland Ave., also 2-lane, all the way to Twin City Highway.

In 1935 Boston Ave., known as Main St. until 1948, deadended at Ninth

Street on the east and at 15th Street on the west. East of 9th Street, there was one house

out in the prairie (where J. W. Sanderson lived at 716 Boston), with a dirt trail going to

it. The 800 block of Atlanta was also a dirt road with two houses on it, deadending a

short distance from Ninth. On the south, the old rice canal right-of-way ran across town

from South Twin City to South 17th at the 400 block, and South 12th, 13th, 14th, 14 1/2,

15th, 16th and 17th all deadended at the rice canal fence. Boston and all other streets

were shelled, with a dirt road here or there going to some house in the prairie. Boston

deadended on the west in front of the old Andrew Johnson residence, which later had to be

torn down to extend Boston to 17th. The street offset in front of Lawyer Donald Moye's

building and the Chamber of Commerce was once an extension of Boston that ran between the

Johnson and Spencer homes and deadended at the old "interurban" depot. As of

1935, the "interurban" double-trolley (known locally by a somewhat vulgar

designation) had already been shut down for three years, and more or less had been

replaced by the Greyhound buses on Twin City that arrived in Nederland at each thirty

minutes after the hour until midnight.

The center of social life in town, especially for school kids, was the

Nederland Pharmacy, the entire business in 1935 consisting of where the lunch counter area

now is. Next door, on the north or even side of the 1100 block of Boston, was Dr. J. C.

Hines' office, then the Theriot and Fortenberry barber shop, B. H. Hall, D. D. S., then

the Nederland Cleaners, the first theatre building, soon to be torn down, the old wooden

post office building, the Haizlip Grocery (which went broke about 1934), another barber

shop, andthe J. H. McNeill Sr. Mercantile Co., in the same building still standing there,

in 1988. About 1937, the McNeill Insurance Co. building was added in a lean-to structure

adjacent to the Modern Barber Shop.

On the south side of Boston, beginning at Twin City, was Albert

Rienstra's Texaco Station, built cater-cornered across the lot, which he later sold to

Goodwin Griffin. The next store, in the new Roach Building, at first housed Mrs. Roach's

beauty shop for a short time, and later Albert Rienstra's Auto Supply, but by 1940 T. W.

Edwards Grocery was there. The narrow building which survived the recent fire was not

built until 1945. The other half of the Roach Building housed Newberry's Barber Shop, with

the old Dolf Club pool hall (known otherwise as the "Bucket of Blood") next

door. Next up the block was the R. C. Mills Grocery, a vacant lot, Minaldi's Shoe Shop in

a wooden building, another vacant lot, then Brookner's Dry Goods at 1151 (which C. M.

Minchew purchased in 1948 and moved his Nederland Home Supply into), then Gardner's

Grocery (located in the old two-story, former Paul Wagner Dry Goods building), and the old

Martin Wagner home on the corner. Earlier in that century, the present-day McNeill

building had been located on that corner, but around 1910, after the old Bradley Bell

Grocery building burned down, the McNeill building was moved across the street, and after

the move, what had formerly been the front door of that building became the back door

thereafter. In back of the McNeill building, Hugh Hooks built a building about 1938 that

housed H. A. Hooks Plumbing Company.

In the 1200 block, across from the side of the McNeill building, stood

the old Oakley Hotel. About 1940, Dick Rienstra bought that corner, moved the hotel

building about 100 feet to the west, where it soon became the Dale Hotel. Rienstra then

built the Roger-Byron Dry Goods building, with the business belonging to Albert Rienstra,

on the corner where the hotel had once stood. There were no other stores on that side of

the block in 1935, only the old Quarles home, and at the end of the block on the corner

stood the old Baptist "tabernacle," once known as the Peveto Baptist Church,

which was a shiplap building with no windows, just some long wooden shutters that swung

upward. That old building did not last long, being soon torn down and replaced by the

two-story First Baptist Church, the concrete foundation of which is still visible on the

bank parking lot. Brick buildings were almost non-existent on Boston in those days, with

only the Wagner (drug store) and Haizlip buildings on the north side of Boston and only

the Brookner and old bank (Yentzen Bakery) buildings on the south side.

On the south side of the 1200 block of Boston, there were only two

buildings in 1935, the first being the old two-story Yentzen Bakery building, which

between 1902-1905 had housed the old defunct First National Bank of Nederland. The other

old building looked like an empty, former feed store building, usually unoccupied,. and

next door to it was the Jack Fortenberry home.

In the 1300 block, there was only one house on the north side, the Geo.

Yentzen home, which stood where the bank now stands, and before that, where the old Orange

Hotel had once stood until it was torn down about 1915. Across the street, the Pat Tynan

home at one time faced Boston, but was moved to the back of the lot to face 14th, year not

recalled. This property on both sides of the street had once been designated in

Nederland's 1897 survey as publicly-owned "Koning" Park, or King's Park, but

about 1915 had passed into private ownership, the south side belonging to Dr. J. H.

Haizlip and Pat Tynan, and the north side apparently belonging to George Yentzen, although

Dick Rienstra purchased the entire north side of the block (including the Yentzen home

which he moved to 1220 Helena), sometime in World War II days.

In 1935, there were three houses in the 1500 block, now principally

occupied by the post office and city hall. The J. B. Cooke, Jr. home occupied the center

of the south side of the block. On the north side, the W. N. Carrington home stood where

the fire station now is. Carrington came to Nederland in 1935 with the intention of

installing a water and sewer system which he would in turn sell out to the new City of

Nederland whenever it incorporated (which it did in 1940). At the opposite end of the

block. adjacent to 15th St., stood the C. X. Johnson home, a house built of black

sandstone blocks.

Along the 300 block of No. Twin City, Oliver Cessac's Cafe, a two-story

wooden building, was adjacent to the pharmacy, occupying space that is now a part of the

drug store. The upstairs of the cafe had a somewhat shady history before 1938, the year

that it (was?) burned down. However, it was soon rebuilt in the exact style that it

formerly was. The upstairs during World War II still had a most shady history, becoming

under Tommy Vinson the biggest gambling den in Midcounty, with the 'house' backed by some

of the town's business men. Vinson not only supervised the gaming room, but he also owned

a dive on No. Twin City near Central Gardens called the "Toboji" (named for his

sons Tommy, Bobby, and Jimmy). In World War II days, Vinson's son Bobby was an

All-American back at West Point, and was later shot down and MIA in Vietnam during the

1960's.

Next door to Cessac's Cafe (and now the Pharmacy parking lot) was Jack

Furby's Garage, which he sold to C. L. Foust about 1945, and Foust in turn to Marvin

Spittler a few years later, who soon moved to Nederland Ave. Then next door was Check

Hensley's beer joint and cat house, a real dive (building still standing and the only one

the "torch" did not burn), which later became Dewey Guilbeaux's Nederland Club,

a pool hall. On the corner of Chicago and Twin City was Bartels' Bakery, and every day it

was a wonderful aroma whenever one walked past it or Yentzen's Bakery at the very moment

the freshly-baked bread was coming out of the oven. Both bakeries apparently went broke

and closed up by 1940, which was just after the big bakeries, Taystee and Rainbow, were

moving into Beaumont. And in order to kill off the smaller bakeries, they would drop the

price of large loaves to ten cents a loaf until all of the small bakers went broke. And

then, as one can well imagine, the price of bread went right back to 20 cents.

In the 400 block of 12th Street, just beyond Hooks Plumbing Co., Dewey

Wallace ran the telephone company and business office in a house at 403 12th St. that has

since been moved away. In 1935, one literally had to "ring the operator" to

place a call, and the operator had to manually connect you with another number by removing

a plug at the switchboard and plugging it into a socket somewhere. Most all phones were on

"party lines." After World War II, Southwestern Bell built a small brick

building (which had been added to many times) at 9th and Nederland Ave., and a dial system

was installed. Before 1948, there were only four numbers in each Nederland telephone

number.

Heading south on Twin City from the Nederland Pharmacy, into the 200

block in 1935, the first 'business' next to Rienstra's Service Station was the old

"Lookout Cafe." which never closed its doors or turned its lights off, 24 hours

of every day. There was a board fence between it and Rienstra's, where all of us paper

boys met at 2:00 A. M. each morning to 'fold' our papers (the "Enterprise"). But

the "goings on" in back of the Lookout, where the floodlights stayed on all

night to illuminate the five or six small, one-room buildings, was just too interesting

for 15-year-old paper boys who especially enjoyed 'peeking' through the cracks in the

fence more than rolling their papers. So help me Hannah - the sailors and prostitutes

romped about in that area at all hours of the night in the nude or in skimpy underwear!

The Lookout probably didn't sell much food, no doubt, but the volume of beer and -- oh

well, enough said! In 1938 and 1939, the Nederland "torch" - whoever he was and

God bless him! -set the Lookout ablaze, just as he did Cessac's, the old Shamrock Inn in

Central Gardens (which often boasted of having 20 women in residence there), and another

dive at the corner of Detroit and Twin City, all of them burning out within months of each

other. When I 'hopped' cars at Nederland Pharmacy in 1936, the women at the Shamrock would

always wait until quarter to eleven at night to order anywhere from 12 to 15 malts that I

had to deliver on a bike along that old narrow highway, with its deep ditches and narrow,

2-foot ledges between the ditches and the road bed, all the way to 4th Avenue in Central

Gardens, two miles from the drug store. Invariably, I'd get back to the Pharmacy at

midnight, and got no pay for the extra hour although sometimes I got a tip.

Asa Spencer was deputy sheriff in Nederland in those days, but had he

done anything to close up the dives and gambling dens, he would have been looking for work

the next day! And since I either hopped cars or threw papers at all hours of the night, I

could easily see why the joints were tolerated. Ships docked at Beaumont, Smith's Bluff,

Port Neches, and Port Arthur in those days, but the sailors came to Nederland to do their

hell-raising. Between 1935 and 1938, there was a Beaumont or Port Arthur taxi loading or

unloading sailors at the drug store every five minutes, day and night. E. C. Whatley, Buck

Gardner, Selmon Gardner, and "Sluggie" Nagle all made their livings hauling

sailors around, and they parked at the drug store in between trips. About two or three

business men had the rest of the town convinced that they would all go broke without the

sailors' patronage, and for some of them, that was probably true. And as a result, one had

to kick the drunk sailors off the sidewalk and the post office steps before he could get

his mail. Very possibly the Theriot-Fortenberry barber shop might have drawn half of its

business from sailors, and of course, I could see that the drug store also did. Before

returning to his ship, nearly every sailor (that is, if sober enough) stopped there to

stock up on cartons of cigarettes, toiletries, and especially the girlie and pulp western

magazines before returning to his ship. Oftentimes, though, the sailors who patronized the

Lookout Cafe, especially if they were foreigners, were drugged and rolled of their wallets

before some taxi carted them off to the docks somewhere. And if one of them complained, he

missed his ship and was hauled off by the law as being "drunk and disorderly"

and was locked up in the tank at the county jail. Bless you, Nederland's

"torch," whoever you were! You cleaned up this town when no one else would!

I remember about 1955, some zealous local preacher, name not recalled,

was passing a dry petition up and down Boston Ave. in an effort to restrict beer sales to

Twin City Highway. He came by the post office and cornered me, and I laughed at him and

asked, "Where were you in 1938?" By 1948, officers had also removed the slot

machines out of the county, and even with a few package stores in town, Nederland was more

like a big Sunday School class by 1955. I think there were only three churches in

Nederland when I moved here in 1935, and you didn't hear a single word out of the

preachers about vice in 1936-1938. After all, Boston Avenue merchants paid the preachers'

salaries as well!

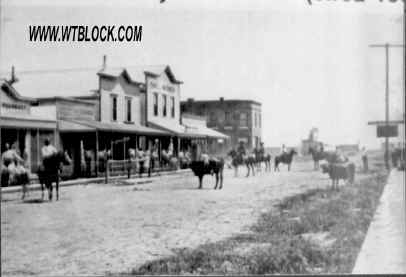

I'm reminded of a tale about another Nederland deputy sheriff that, if

I don't tell it now while I'm thinking of it, I'll forget it sure. In 1906, the year that

Grandma Sweeney, my mother, and the rest of the Sweeney family moved to Nederland (also

the Haizlips), the 'law west of the Neches" in those days was Deputy Sheriff

"Smoky" Hemmingway. If one heard a ting-a-ling, bell-like noises in Nederland in

1906, it most probably was "Smoky's" spurs clanging along the board sidewalks

along Main Street, now Boston. There were three saloons, Peek's, Steiner's, and Freeman's,

in the 1100 block of Boston until 1909, when all of them were closed up. I remember my

uncles laughing about "Smoky's hardware." He wore two gun belts, each slung low

with scabbards tied down at the knees, and inside of them were two pearl-handled,

45-calibar pistols that would have done justice to "Wild Bill" Hickok.

"Smoky" made his rounds of the saloons several times daily, and even more on

weekends and paydays when the rice field laborers, Spindletop roughnecks, and the

"Lazy-0" cowpokes filled up the bars.

The "Lazy-0" ranch headquarters was at the McFaddin Canal Co.

office on what is now Dupont Road, 4 miles north of Nederland. I've also been told that

every saloon bartender's first job each morning was to go to the Singleton Meat Market

nearby to buy about ten pounds of beef to be ground up into ground meat, mixed up with

onions and garlic. It seems that the early Dutchmen, Germans, and Austrians in town, upon

ordering a beer or drink, expected also to find a platter of free ground meat on the

counter, a loaf of rye or pumpernickel bread, and a serving knife for spreading the raw

meat on the bread. And if the saloon did not furnish the raw meat and bread, it didn't

stay in business too long. At least, not nearly as long as the swarm of house flies that

hovered over the meat platter.

But back to Smoky. It seems the deputy made his rounds one day and

found a drunk and disorderly "Lazy-0" cowboy, waving his gun, cussing, and

storming around inside of Steiner's Saloon. "Smoky" told the cowboy he would

have to check his gun with him, but the cowpoke refused, and roaring mad, told the deputy

he would meet him out front in the street and they "would shoot it out." But

"Smoky" refused, telling him that he was on duty and very busy, and added,

"If it's all the same to you, I'll meet you at high noon tomorrow out at the

"Double Bridges," and we will shoot it out, provided you get on your horse now

and head back to the ranch."

The cowboy nodded in agreement, got on his horse and rode north toward

the ranch. Now in the early days, the "Double Bridges" were located about where

the Unocal plant road intersects Highway 366. And in 1906, the two bridges crossed over

the east and west rice canals, about 100 yards apart and near the "Y," where the

canals joined the main river flume from the pumping plant on the river. By 1923, those

canals were long abandoned, and in fact, the Unocal plant road was made by grading

together and leveling the two levees of the old abandoned river flume.

By 11:00 o'clock the next morning, one could see many of the Dutchmen

and all of the other "local yokels," riding their buggies, wagons, hacks, on

horseback, side-saddle, or on foot or other conveyance, bound for the "Double

Bridges," and each with a thirst for blood in his eyeballs. Just as one would go to

the refinery today, they went out the present-day Helena Street extension, which was then

a dirt road going to the pumping plant on the Staffen property. Many of the sightseers

waited over an hour, and about a quarter to twelve, they spotted the McFaddin cowpoke,

riding along the railroad right-of-way en route to the "Double Bridges." The

crowd waited until about 12:45 P. M., but two-gun "Smoky" never showed up.

Instead, he turned in his badge a few days later, unable to show his face in Nederland

anymore, and shortly afterward he left the county for greener pastures.

But back to the Nederland business houses of 1935. Going south into the

200 block of Twin City, the next building beyond the old "Lookout Cafe" was the

old Freeman home, which still stands on the corner of Atlanta. In the 100 block, J. C.

Kelly ran a Pure Oil bulk distributing concern on the corner and on the same lot where

earlier Johnny Ware had had the post office (the lot then belonged to my mother), and

where Thompson Grocery would be built during the 1940's. Next, Charlie Chamberlain ran a

small store next door to the old Biermortt home, which stood on the corner of Nederland

Avenue.

Nederland Ave., going west from Twin City, was certainly not much of a

thoroughfare for business houses in 1935, being only a shelled street. But then so was

Main Street in those days. In back of the Biermortt home (where Exxon is today) stood

Howard England's cabinet shop. On the corner of 12th Street was Giebelstein's hamburger

emporium, which served mostly school children in 1935. When I was a paper carrier in

1936-1937, I recall stopping at Giebelstein's one evening about dark and ordering four

hamburgers and two tall, strawberry Nehis, which cost altogether 30 cents, hamburgers and

bottle drinks being 5c each in those days. Mrs. Giebelstein looked at me kind of peculiar,

especially while I was eating, because I went through those hamburgers and drinks like a

circle saw through plywood, in about 7 minutes flat. It was when I ordered four more

hamburgers and two more Nehis that her eyeballs fell out and she almost fainted.

Altogether, I ate eight hamburgers and drank four Nehis, those TALL ones, that finally

filled my gut at a cost of 60 cents.

Also in 1937, at Nederland Ave. and Twin City, Babe Vanderweg built the

cafe and drive-in that J. E. Pitre would operate as Pitre's Cafe for about the next

fifteen years. Except that it sold beer and had about a dozen slot machines in it, Pitre's

was one of the more respectable places in early-day Nederland. I and lots of other

soldiers hang out there whenever we were home on leave during World War II (which for me

was almost every weekend while I was stationed at Galveston). I helped build the Pitre

building. The original building was stucco masonry, and I pulled a mortar hoe, mixing

stucco cement, for $2.00 for a 10-hour day. But that was big pay - I had worked for 10

cents an hour on some occasions, particularly at the drug store. For months on end, I

could not find work anywhere at any price.

On the east side, where the railroad tracks intersected Nederland

Avenue, remnants of the old Nederland Rice Milling Company still stood behind the old

Jake Doornbos home, but I think it was only the old, 4-story elevator that still stood,

where Pete Doornbos operated a feed store for about one year around 1936. Across the

street, in the building that later became Hammock's paint store, stood the old Gulf States

Utilities Co. offices and ice house. In those days, a locomotive delivered a box car of

ice to the back of that building daily. A railroad spur and siding ran across the 100

block of 11th St. to the back of the building, and every morning Mooch Ingwersen and a

couple of other men had to unload that box car of ice that was made in Beaumont. In

addition, Iiams Ice Co. had a plant on North Twin City, near the railroad underpass and

Sun Oil gate, that made 20 tons of ice daily, all of which were sold in Nederland and Port

Neches. And the Texas Co. (Texaco) ice plant in Port Neches made 20 tons of ice daily

also, mostly for plant use. When I moved to Nederland, H. P. Youmans peddled ice door to

door, packing 100-lb. blocks of the stuff on his back, from a small truck. Twenty years

later, he owned Youmans Insurance and Real Estate, at first at 1220 Boston, and later at

3000 Nederland Ave., from which location he began developing the 300 lots in Youmans

Addition in 1953.

I keep repeating "when I came to Nederland in 1935" as if I

never saw Nederland before that year. Actually, I was in Nederland once or twice a week as

far back as I can remember since my mother had six brothers and sisters living in

Nederland. My father had three brothers and sisters living here, the M. G. Block, Con

Wagner, and Henry Spurlock families, as well as several brothers-in-law and sisters-in-law

from his first wife, among them Lawrence, Klaas, and John Koelemay, George Rienstra, and

S. R. Carter. One thing I recall quite vividly from that period was when the old

two-story, Martin Koelemay home at 2000 Helena burned down in 1928. Until 1948, Helena

Street was Koelemay Road. In 1935, it too was shelled a part of the way beyond the

"interurban" right-of-way, but soon deteriorated to two thin ribbons of shell

with bitter weeds growing in between. When Koelemay Road reached 27th Street, it turned

abruptly at the Emmett Smith home and continued north, still two threads of shell, until

it deadended at the John Koelemay dairy at Canal Street.

There were two large dairies where Helena intersected what is now 27th.

The house of one of them, at 2304 Helena, is still there. My grandmother Block's brother,

Emory A. "Bud" Smith, built that house about 1900 and started a dairy there, but

by 1920, the dairy had passed to his son. Emmett A. Smith. If one turned south at what is

now 27th, he would end up in the cow lot of the John Henderson dairy, only one block from

the intersection. But Koelemay Road, with its two strips of shell and the bitter weeds,

only turned north at that point to deadend at the Koelemay Dairy. John Koelemay's dairy

was the second largest in Nederland, and all the land where C. O. Wilson Middle School now

is was once a part of its cow pasture. The dairy worked quite a few employees during the

1920's-1930's and kept three trucks delivering milk on its retail milk routes in Beaumont.

I'm not sure how many gallons it bottled daily in quart bottles, but probably close to

five hundred gallons. In addition, John Koelemay was quite a successful Satsuma orange

grower. He had about 20 acres of large, bearing trees, each around 20 feet tall. During

the winter, he had to keep smudge pots burning in the orchard during sub-freezing weather.

And that is what eventually happened to the orchard. Temperatures got down to about 12

degrees one year around 1940, and he lost all of the trees. How they survived the blizzard

of January, 1935, is beyond me because temperatures went to 9 degrees and stayed there for

three days. But he saved the orchard that time, only to lose it later.

In 1935, Dick Rienstra was the manager of the Barnes Feed Company,

which was a Port Arthur concern, located in what is now the south building of the Setzer

Supply Co., alongside the railroad track, and the north building was the Koelemay Grain

Co, operated by Lawrence Koelemay (my father's brother-in-law) until 1937, and by Martin

Koelemay, his brother, until 1943, when it was sold to H. W. Setzer. The old north

building is unique in Nederland history, for in 1900, it was built to store sacked rice in

before it was shipped somewhere for milling. After Nederland Rice Milling Co. was built in

1904, there was no longer any need to store rough rice to await shipment out of town.

Patrons who visit Setzer's today might take note of the 2" X 6" center match

flooring in the building, a lumber item that has not been manufactured for the last fifty

years.

Across from the side of the old Koelemay Grain Co., at the southeast

corner of 11th and Boston, E. P. Delong operated an auto repair garage in 1935 in a

two-story, wooden building. About 1938, Delong sold the business to George Netterville,

who operated the garage until his death, sometime in the 1940's. Remnants of the old

garage's concrete foundation are still visible on that corner. Across the street, on the

northeast corner, was the building that Johnny Ware built about 1928 to house the post

office and his grocery store in. In 1933, after Bill Haizlip became the Democrat

postmaster under Pres. Roosevelt, the post office was moved to an old wooden building at

1144 Boston (where Dr. J. H. Haizlip's office was), which preceded the brick building

built in 1940 and still standing. After Ware died in 1932, C. X. Johnson served as interim

acting postmaster for about one year. Ware's widow, Mrs. John Ware, continued to run her

store until her death during the early 1950's, after which the building was torn down. The

last person to occupy the old post office side of the building was Dr. Felix Walters in

1954, before he moved his clinic to the L. Ingwersen building at 1135 Boston (and about 15

years later to 13th and Franklin).

There are two other businesses of pre-World War II Nederland that

should be mentioned, although I am sure there will be others I will recognize before

closing this chapter. About 1938, Tony Guzardo began the Guzardo Feed Store on Twin City

in the same building it has occupied for fifty years. Guzardo also had a feed store in

Port Acres, and after World War II, he turned his Nederland store over to his son,

Rayford, devoting his full time thereafter to his Port Acres store until his retirement.

About the same time, the Harbour Grocery was begun in a wooden building on the southwest

corner of Sou. 12th and Nederland Ave., on the lot where Baker-Williford Pharmacy

currently stands, but the Harbour Grocery was either sold or went out of business about

1945.

Generally, these were the Nederland businesses before World War II

began. Occasionally, there was a second drug store in town. A man named McKee ran a store

for a year or two, about 1937-1938, at about 1135 Boston and eventually went broke, unable

to puncture the Nederland Pharmacy competition. About 1936, a man named Dodson opened a

drug store in the Haizlip building at 1152 Boston, and he too went broke within a year.

This was the same man who bought five acres of our old Block home property at the cemetery

in Port Neches, which included the house I was born in, and in 1937 he tore down the house

and piled up and burned a lot of the old furniture that was left in it. Among the things

he burned, things that we couldn't bring to Nederland because we had no room for them,

were old dining room and kitchen tables and chairs, both of the tables more than 100 years

old; our old RCA Victrola and lots of records, an old peddle-pumped organ; Dora Koelemay

Block's zither, which she had brought with her from Holland in 1898, as well as her old

wooden steamer trunk which still bore the notation: "From Antwerp to Nederland,

Texas." In 1898-1899, Dora Koelemay had accompanied many of the waltz and polka

dances on her zither (auto-harp) at the old Orange Hotel, which the Koelemay family

managed when they first came from Holland. I don't recall what else might have been

burned, but we left an attic filled with a half-century's accumulation of antique

furniture that we had no room for when we moved to Nederland in 1935.

The business community did not change much during the war, perhaps

because there was no defense priority for building materials in the private sector. Before

the war, two or three of the old cat houses that burned in 1938 were rebuilt, but vice did

not return to Nederland so far as I know. After the old Lookout burned, a Mrs. Smith, Mrs.

O. S. Johnson's mother, built a respectable night club in place of it, and during the

1950's, that building became Roebuck's Pool Hall. Inez Freeman Eastis and her husband,

Gordon Eastis, built and operated a liquor store in the concrete block building next door

to the old Freeman home at Twin City and Atlanta, but it went out of business after Eastis

died in about 1955. The dive that burned in 1938 at the corner of Detroit and Twin City

was rebuilt and served as a cafe during the war. Later, it became a lumber company office.

About the time the war started, Albert Rienstra sold out his service

station to Goodwin Griffin. The old wooden building was soon torn down and replaced by a

brick building, remaining a Texaco station. T. W. Edwards operated his store in the Roach

building from 1940 until about 1947, when he sold out to Luther Richey of Warren, who

promptly went broke within a year. About 1948, a White Auto Store opened at that location

in the Roach building and stayed in business about ten years. Walter Resch and a partner,

name not recalled, operated the White store, and both of them left Nederland after the

store closed. About 1946, F. A. Roach sold the Nederland Pharmcy to Marvin and Ella

Wagner. Mr. Wagner died the following year, but Mrs. Wagner, later Mrs. Killebrew,

operated the business for about the next 25 years, before selling out to Kenneth

Sheffield. During the early 1960's, she purchased the adjacent Cessac and Nederland Motor

Company property, and later Mrs. Killebrew enlarged the pharmacy to its present size.

The name T. W. Edwards reminds me of another incident when World War II

started. On the Sunday that the Japs bombed Pearl Harbor, my mother, recalling some of her

own experiences in World War I and realizing we were already caught up in the next war,

decided to order up a quantity of sugar and green coffee beans. So the next morning, my

brother, Everett Staffen, and I were at Edwards store when it opened on Monday morning,

and we ordered two 130-pound sacks of green coffee beans and two 100-pound sacks of sugar.

My brother, realizing as well that America would be cut off from its supply of natural

rubber, ordered four new tires for his new 1941 Ford pickup truck, the tires to be stored

at home until needed. Two days later, we backed up to Edwards Store to pick up the sacks,

and as we carried them out to the truck, a nearby bystander, well-known for probing into

family affairs not his own, wanted to know what was in the sacks. We told him, "Cow

feed." He rejoined, "But Edwards doesn't handle cow feed." "We know,

but he'll order it for you if you want him to," my brother retorted, leaving the

busybody with mouth hanging open. The coffee and sugar lasted my mother and sister

throughout the war although it didn't do my brothers and I any good, all of us soon being

gone off to help fight the war. The aroma of coffee beans roasting often permeated the air

around Ninth Street during the war years, advising the neighbors that the Blocks still had

some coffee on hand.

About 1939, Dick Rienstra bought the two-story, brick Yentzen Bakery

building (which in 1902 had been the First National Bank building), where he founded D. X.

Rienstra Feed and Supply Co. About 1946, three new store buildings were added next door

between 1211 and 1219 Boston. Rienstra founded D. X. Rienstra Hardware Co. next door.

Nederland State Bank organized in 1947 and occupied the middle building for several years.

Woodville mercantile interests provided the capital and obtained the state charter, and

promptly sent W. W. Cruse to Nederland as the new vice-president and chief operating

officer, as well as J. W. Willson of Chester as the first cashier. C. M. Minchew founded

the Nederland Home Supply in the third building.

Dick Rienstra soon afterward sold the hardware store to Earl Kitchen of

Port Neches and signed a ten-year agreement not to re-enter the hardware business in

Nederland. Then he tore down the old bakery building and built the present store building,

at the southwest corner of 12th and Boston, in which he began the Rienstra Furniture Co.

In 1946, M. B. Jeffcoat moved to Midcounty and started five and dime stores in Nederland,

Port Neches, and Groves. His Nederland store was in a new brick building wedged in at 1147

Boston, between Minaldi's Shoe Shop and Brookner's Dry Goods. In 1947, A. C. McLemore

moved to Nederland from Alvin, Texas, and he soon bought all three of the Jeffcoat stores.

About 1956, when Dick Rienstra built a new store building at 1344 Boston, he moved the

furniture store into it, where it still remains, and McLemore's moved into the old

furniture building at 1204 Boston. McLemore died about 1962, and his three stores were

eventually sold to another firm who promptly went broke in Nederland.

Back in the 1100 block of Boston there were other significant business

changes. Minaldi Shoe Shop, which began before 1940, operated for twenty years in an old

wooden building before removing it and building their present brick building. Next door,

Delmar Mauldin operated a small watch repair business for about 20 years. After Fred Roach

sold the pharmacy, he promptly opened Roach Insurance and Real Estate in the old barber

shop building at 1119 Boston. The insurance firm remained in business until about 1960 and

eventually was managed by J. B. "Red" Woods of Beaumont, who subsequently had a

carpet shop on Nederland Avenue. In 1946, Roach also built an addition on the east side of

the building, about 12 feet wide, in which Mr. and Mrs. A. H. Callihan founded the

Callihan Insurance Agency in 1946. At that time Callihan owned and was developing Westside

addition on Gary and Franklin Streets. He died in 1950, after which Mrs. Callihan

liquidated her interests and moved away. Shortly afterward, Dr. Fred Roach, Jr., began his

dental practice in that building and remained there perhaps five years before relocating

at 412 Nederland Avenue. The Roach building burned about 1983, and the 12-foot addition

that Dr. Roach and Callihan formerly occupied was all that survived the fire.

About 1945, Elmore Creswell opened an appliance store in the building

that once had housed the old Dolf Club pool hall, and he also opened an appliance store in

Port Neches. These stores remained in business between 20 and 25 years. Also about 1940,

Ludolph Ingwersen of Port Arthur (Mooch's brother) bought the old R. C. Mills' Grocery

building next door after Mills died, and he remodeled it, doubling its size into two store

spaces. About 1946, Dr. Philip Weisbach (now a Beaumont ophthalmologist) occupied the old

Mills site and stayed there about three years before he returned to medical school to

specialize. Dr. Weisbach once remarked that he was taking in $5,000 a month at that

location at $5 a visit, which was not bad in 1947, even for a doctor. He turned his

practice over to a Dr. R. J. Seamons in 1949, who did not take care of it, leaving after

three years for the V. A. hospital in Waco. In 1948, Minchew bought the old 2-story, brick

Brookner building at 1151 Boston (after N. Brookner closed up and moved to Port Arthur),

remodeled the building and moved his Nederland Home Supply appliance firm into it.

In 1940, Mrs. Mattie Gardner tore down the old 2-story, wooden building

in which her grocery was housed and replaced it with a brick building. About 1950, she

sold out to her nephew, J. C. Barnes, and she opened a dry cleaning plant in the old

vacant Wagner home next door. This business operated until about 1962 when Mrs. Garner

retired and moved to Honey Island. Barnes operated Gardner's Grocery until his death in

1979, after which the business was liquidated.

The 1940's would witness many changes across the street as well. Dr. J.

C. Hines, who had been next door to Nederland Pharmacy for about twelve years, chose to

retire about 1945 and he turned his practice over to Dr. Robert Moore. After a few years

there, he and Dr. B. H. Hall, the dentist, moved to the new Hammock building, which covers

the south side of the 1400 block of Nederland Avenue, and Maurice Harvill opened his

Maurice the Florist business next door to the drug store. About 1955, Harvill moved to one

side of the Ingwersen building, where he remained in business for about the next eight

years.

Lowell Morgan kept his Nederland Cleaners in the old wooden building at

1124-1128 Boston location until World War II, after which he relocated on Nederland Avenue

after he returned from military service. Mrs. F. W. Bridgeman of Beaumont then built the

brick Bridgeman building, containing two store sites, on that spot in 1948. Mrs. Pearl

Niewohner then opened her Niewohner's Dress Shop on one side, and in 1954, she sold out to

Mrs. Polly Speriky, who then operated Speriky's Dress Shop for about twelve years before

selling out to Mrs. Verble Grimes, who soon after closed up the women's apparel store.

Next door at 1128, Gaston Mayer of Port Arthur opened Mayer's Men's

Wear in 1949, and he remained in that building perhaps two or three years before he closed

up and moved back to Port Arthur. "Goodie" Griffin then opened Griffin's Men's

Wear in the same building in 1953 and remained in business for perhaps five years before

he too closed up. About 1948, the old, rat-infested Rio Theatre building, a wooden

structure, was torn down, and the old theatre site at 1136 Boston has remained a vacant

lot ever since. About 1940, J. H. McNeill, Jr. built the brick building at 1140 Boston,

which was at first occupied by People's Gas Co. and later by its successor, Southern Union

Gas Co., until about 1960. In 1955, whenever the post office was relocated at 1320 Boston,

Whelply's Jewelry, which until then had been located at 1148 Boston, moved next door into

the old post office location. About 1940, Bill Haizlip had started the Nederland Furniture

Co. at 1152 Boston in the same building where, during the early 1930's, he and his

brother, John Haizlip, had gone broke in the grocery business, and where Dodson had also

gone broke in the pharmacy business. Boy, that old "Great Depression" took some

toll of the early Nederland business houses, and everywhere else for that matter!

Jack Fortenberry and Lovelace Theriot finally split up the barbering

partnership, with the former spending the remainder of his barbering career in the Modern

Barber Shop, adjacent to Nederland Furniture Co. About 1936 James McNeill Jr. closed up a

grocery store he had been operating in Port Neches. He then built a "lean-to"

building onto Jack Fortenberry's barber shop and began an insurance agency. McNeill

Insurance remained in that building until about 1955, at which time the agency moved into

a new red brick building about half the size of the present building.

Around 1945, J. H. McNeill, Sr., already approaching 80 years old, was

still active in his J. H. McNeill and Co. mercantile firm, but for years the active

management of the company had been performed by J. Berthold Cooke, Jr. During World War I,

Cooke had been McNeill's son-in-law, married to the only McNeill daughter, but she died of

"Spanish flu" soon after her marriage. J. B. Cooke died around 1948, and his

widow kept the store open a few more years, finally liquidating the business about 1954.

McNeill Sr. had long before broke up housekeeping in his large home after the death of his

wife, and about 1944 he leased the palatial residence to Weldon Davis for the new Davis

Funeral Home. Davis operated the mortuary there for more than thirty years, eventually

selling out to Clayton-Thompson shortly before his death about 1980.

About 1937, J. H. McNeill, Jr., built his home in the 300 block of 13th

Street in which his widow still resides.

In the same year, although I had been living in Nederland for more than

a year, I had still been riding my bicycle to attend school in Port Neches, that is, until

January, 1937, when I transferred for my last semester to Nederland High School. Hence,

although I have a Port Neches High School senior class ring, I have a diploma from

Nederland High School. I had just had a wreck with a car while I was delivering papers on

my bicycle, and although I was bruised only slightly, my bike was a total loss. That

summer, I worked at the Smith Bluff Lumber Company, which until 1940, was located at 11th

and Detroit, where Ritter Lumber Company now is. Off and on, I worked there altogether

about three years, I suppose. One Monday morning, a locomotive switched a box car onto the

Smith Bluff Lumber Co. siding, and Joe Block and I were each handed two sets of brick

tongs apiece and told to unload it. Hence, we knew our week's work was cut out for us, as

the box car would have to loaded with brick, 35,000 of them. All week long, for eight

round trips a day, we would back a long, bobtail truck up to the box car; load it with

about 800 bricks, carrying seven 5-pound bricks (35 lbs.) in each hand; drive over to the

site where the foundation of the J. H. McNeill, Jr., home was underway; unload the bricks,

and drive back to the box car for the next load. We were also told that the box car had to

be empty by Friday afternoon, or demurrage of $60 had to be paid for it over the weekend.

I guess, considering the number of brick in it, we must have averaged about 7,000 bricks a

day.

Come Friday afternoon, Joe and I were so happy because only one load of

about 800 bricks was left in the box car, equal to about an hour and one-half of work.

Then suddenly a switch engine began sidetracking another box car alongside of the one we

were working in. We ran to the lumber company office and inquired, "What's in that

new box car we just received--lumber for the McNeill home?" "No," was the

response, "The lumber for the house will be here next week. I didn't have the heart

to tell you that this car has 35,000 brown face brick for the outside of the McNeill

house, but you won't have to start on it until Monday morning." So Joe and I had

another slave-killing job during the following week. I don't believe I have ever been so

tired in my life as I was each night after I had been unloading bricks.

John Staffen, my half-brother's Everett's uncle, had started the Smith

Bluff Lumber Co. during the 1920's at 11th and Detroit in the huge old building that

belonged to Lawrence Koelemay. The latter had apparently done quite well in the feed

business up until 1934 and was even a director of the First National Bank of Port Neches

at that time. But his son, James Koelemay, convinced his father that they could get richer

a lot faster if they became a dealer for Majestic radios. If any person, living today and

only acquainted with light-weight, transistor sets, had never seen a Majestic High-boy

radio of 1930, he would never believe it. The power transformer alone in that model

weighed over 20 pounds, and the rectifier tubes, chokes, and condenser banks in the power

supply of that model added another 35 pounds--not counting the weight of the radio and

heavy cabinet. The radio per se in that model was not so heavy, perhaps 20 pounds, but it

was large and bulky, with a bank of tuning condensers about 14" or 16" long and

several large, glass vacuum tubes (the type with a sharp point on the top where the glass

had been sealed by heat after the air had been pumped out) eight inches high, roughly the

size of a 250 watt light bulb. The Majestic radios stood on four short legs, but weighed

so much, a real monstrosity of about 130 pounds, that it usually took two men to load or

unload one of them from a truck.

Anyway, Lawrence Koelemay borrowed about $15,000 for a franchise and to

pay cash for his first shipment, a box car load of radios, and after he got them, James

couldn't sell them. L. Koelemay had to put up the lumber company land and building as

collateral for the loan, which the Port Neches bank promptly foreclosed on and took back.

And he also had a lien on the feed store business. This forced Koelemay into bankruptcy,

and the family left town one day, moved to Shreveport, where they opened a wholesale radio

parts business soon afterward and prospered quite handsomely in that field. I don't know

what eventually happened to the big shipment of Majestic radios which were stored in the

feed store, but I presume they were auctioned off. Martin Koelemay, Lawrence's brother,

took over the feed store and operated it until 1943, when H. W. Setzer bought out the

business.

About 1940, a Houston wholesale building supply firm, George C. Vaughan

and Sons, was eyeing Nederland as a base of supply for its customers in Southeast Texas

and Southwest Louisiana. They bought the lumber company building from the Port Neches bank

in 1941, but gave the old lumber company building to Smith Bluff Lumber Co., provided the

old building was removed from the site within 90 days. Staffen also owned the 18-acre

tract of land where Highland Park School and Jones Marine business are located, so in

October, 1941, as the old building was being torn down, John Staffen began building the

new Smith Bluff Lumber Co. in the building later to be purchased by Jones Rambler Co.

about 1956. And the lumber company reopened on that site in January, 1942, just as the war

came on and lumber, nails, all metals and hardware, became unobtainable except with a

defense priority. Staffen was able to keep the lumber company open for a part of the war

years. He was able to buy about 200,000 board feet of green lumber from some small

"peckerwood' sawmill in Louisiana. Then he air-dried the green lumber on his property

and dressed it with an old tractor-driven sawmill planer that he had purchased somewhere.

As early as 1937, W. K. McCauley had started McCauley Lumbet Co. on

11th Street, north of Smith Bluff Lumber, and when he moved to Houston during World War

II, his brother-in-law, B. A. Ritter, began operating the business as Ritter-McCauley

Lumber Co. About 1970, after the old Vaughan building had lain vacant a couple years,

Ritter Lumber Company took over that location, soon becoming Nederland's principal retail

lumber firm, and gradually expanding into the home construction field as well.

Three other lumber businesses developed in Nederland after World War

II. L. B. Nicholson built Nicholson Building Supply next door to Guzardo Feed on South

Twin City. Nicholson died about 1965, and the business was sold. On Memorial Highway,

across from the airport, two other lumber firms was established after World War II. S. E.

Lewis organized Lewis Builders' Supply, which was managed by his son-in-law, Thornton

Niklas, and Irby Basco began the Basco-McAlister Lumber Company a short distance to the

north. For years, Basco produced his own lumber, as he owned a small sawmill across Pine

Island Bayou at Lumberton.

George C. Vaughan and Sons built their first building in Nederland in

1942, just about the time the war started. The firm dealt principally in windows, doors,

moldings, flooring, and similar materials, and the business was managed by W. F.

Ricketts, with W. L. Kelly and Spencer Ritchie as the outside salesmen. George C. Vaughan

continued to expand until after 1960, by which time the five buildings had been built and

the firm exployed more than thirty employees and delivered merchandise in its three

18-wheeler trucks. No one dreamed that Vaughan was in Nederland other than permanently,

when suddenly in 1968, Vaughan chose to shut down its Nederland operation and handle its

delivery territories out of Houston. The old Vaughan buildings remained vacant several

years, but were finally purchased about 1972 by Ritter Lumber Company.

After selling out his hardware business to Earl Kitchen at the end of

World War II, Dick Rienstra purchased Albert Rienstra's old Roger-Byron Dry Goods

business, and renamed it Rienstra Dry Goods Co. It was then located on the corner of 12th

and Boston, next to the Dale Hotel in an asbestos-sided building, and Albert Rienstra

built a brick building on 12th, across from H. A. Hooks Plumbing Co., and opened a

hardware store in it about 1948. Apparently, Dick Rienstra did not like retailing dry

goods, for he soon sold Rienstra's Dry Goods back to Albert Rienstra. About 1951, the two

brothers tore down the old asbestos-sided building, and then replaced it with a brick

building that housed Rienstra's Dry Goods firm for more than 25 years. About 1977, Albert

Rienstra liquidated his inventory and retired. An office in the back of the Rienstra

building, facing 12th, housed the law offices of Guy Carriker, Nederland's first permanent

attorney-at-law, until his death in the late 1960's.

Several other new Nederland businesses owed their origins to the

aftermath of World War II. In 1947, Alvin Barr, Farris Block, L. B. Nicholson and others

put up about $8,000 and organized the Nederland Publishing Co., and Dick Rienstra built

the building at 1220 Boston, next door to the Dale Hotel, to house the new firm in. On

about three occasions, that building was added to until it finally reached the alley. The

printing company began published a weekly newspaper, the "Midcounty Review,"

using a new invention or technique, called offset printing, which was a photographic

process rather than hot type. In fact, if I recall correctly, the "Midcounty

Review" was the first publication in the county put out by that process, that soon

signaled the demise of the old hot-type Linotype machine and the powerful typesetters'

unions. The company also published a Groves newspaper during its early years, with Farris

Block as editor of both publications. About 1955, Block resigned, sold his stock to Alvin

Barr, and moved to Houston. Although Block never endorsed any local candidate, he did

endorse Lyndon Johnson in the senate race and Adlai Stevenson for president at a time when

there was a strong conservative reaction taking place in Nederland. And when Block was

accused by one of the stockholders of supporting certain local candidates, his response

was to sell out and move away.

At that time, Barr acquired a controlling interest in Nederland

Publishing Co. About 1960, he tore down the old Barr apartment buildings that stood in

back of his home, and he built the new Nederland Publishing building at 14th and Atlanta.

Gradually, Barr acquired all of the outstanding stock of the company. About 1964, he sold

the "Midcounty Review" to what is now the "Midcounty Chronicle." Barr

managed the firm until his death in Sept., 1981, after which his family sold out to a

Beaumont company. After the bank acquired the land and equipment through foreclosure,

David Willis purchased the Nederland Publishing and Office Supply and operates it to the

present day (1988).

Simultaneous with the founding of the printing firm, three other brick

buildings went up next door to it on Boston, at 1224-1232. The Home Laundry and

Nederland's first washeteria occupied one of them. Youman's Insurance Co. began at 1232

Boston. In fact, the Nederland Chamber of Commerce started out in the old McNeill

Insurance building, but later removed to the Youmans Insurance building when the latter

firm moved to the 3000 block of Nederland Avenue. In 1953, H. P. Youmans bought the 90

acres of land that had formerly been the John Henderson dairy, and immediately, Youmans

began building houses in the Youmans No. 1 Addition. Ultimately, he would build about 300

homes in the various Youmans additions, which kept his insurance firm more of a real

estate firm than anything else. The company was liquidated about 1975, several years after

Mr. Youmans' death.

Also in about 1947, J. B. Baker and Jimmy Williford arrived in

Nederland from Galveston, and founded Baker-Williford Pharmacy in a new building built for

them by L. Theriot at 1204 Nederland Ave. This was the first drug store that was

successful in bucking the competition proffered by Nederland Pharmacy. In early days, this

firm offered 5 cent coffee at their lunch counter, which was the price of "depression

coffee" of 1935, and this alone attracted a great deal of new traffic into the new

drug store. J. B. Baker moved back to Galveston after a few years (although he may have

retained a silent interest), leaving Jimmy Williford as the sole proprietor. About 1956,

the pharmacy purchased the lots across the street and moved a wooden building away from

the property. This was the same building that had been occupied by Harbour's Grocery

around 1938-1940. In 1945, James Threadgill began a store there and remained until he

moved away in 1948. About 1950, Chester Bartels (who had operated a bakery in Nederland

during the 1930's) began an electric company in it, and in 1953, added Nederland's first

TV dealership. After a few years, he built some small business houses adjacent to the

telephone building in 800 block of Nederland Ave., moved his business there, but died soon

afterward. Also around 1953, Charles Stakes founded the Modern TV and Appliance Co. which

has now been in business in the 400 block of Nederland Ave for about 35 years.

B. C. Miller built the Miller Electric Co. at 15th and Nederland Ave.

before World War II, and for many years, handled appliances as well. He built his firm

into the most successful industrial electric firm in town. Lowell O. Morgan reopened his

Nederland Cleaners in a quonset building across Nederland Ave. from Miller Electric

Company, and remained in business there until his death about 1968.

About 1951, a young man named Dan Ryder of Port Neches opened a Western

Auto Store next door to Baker-Williford Pharmacy at 1212 Nederland Ave. I recall being in

the Jaycees with Ryder about 1952. About 1954, he failed to come home one night, and his

family found him later slumped in the chair at his desk, with a single gunshot wound in

the head. Apparently, he had become distressed over finances. Western Auto remained there

for many years, eventually moving to the 2500 block of Nederland Avenue, into the building

vacated by Hughes Market Basket.

If the writer were asked which firm had proven to be the most

phenomenal success in Nederland, it would have to be Ed Hughes and his Market Basket

chain. He began merchandising on Nederland Ave. in 1954 on a moderate scale and with his

former partner, Bruce Thompson, built Market Basket Stores into one of two area grocery

chains. About 1978, Ed Hughes developed the Holland Square shopping center at 27th and

Nederland Ave. and moved his Hughes Market Basket into a modern new building at that

location. Earlier, he had built the Marion Cafeteria (where Eckard is now located) as the

first business in that shopping center, but a host of new fast food places soon relieved

it of most of its business. Hughes also owns business property begun by Joe Bean across

27th Street, as well as the Pompano Club in Port Neches. A few years ago, Hughes sold out

his interests in the Market Basket Stores to his former partner, Thompson, retaining only

his Nederland property.

An incident similar to Ryder's death occurred at Boone's Sheet Metal

Co., which began in the 1000 block of Nederland Ave. about 1955. About 1966, Boone, a

Groves resident, sold his building site to the Weingarten Realty Co. for a shopping

center, and Boone built a new building at the corner of 8th and Nederland Ave. He too must

have suffered subsequent financial woes, for soon afterward his family found him inside

the building, likewise dead of a gunshot wound. Both the Ryder and Boone deaths were ruled

suicidal.

Dr. Ed. Streetman's veterinary clinic has now been on Nederland Avenue

for well over forty years. Speaking of Dr. Streetman reminds me of another aspect of

Nederland's history -- the dairies and the dipping vats of 1936. In 1935, the State of

Texas decreed that all livestock had to be dipped every week for a span of several weeks

during the spring of 1936 (I forget exactly how long) in order to to eradicate fever ticks

(the insects in the ears of cattle and other animals) and tick fever, which had stricken

thousands of cattle in West Texas and Mexico. Strict quarantines were placed on animal

movements that year - both interstate and intrastate. East of the railroad, two dipping

vats were built, one on Babe Vanderweg property in the 800 block of Nederland Ave. (next

to Jones Marine) and another vat on Kitchen Road (now Merriman in Port Neches, near the

intersection of Highway 366). Other vats were built on the west side of Nederland, all of

them under the jurisdiction of Vanderweg. Dipping was mandatory, with the prospect of

undipped cattle being shot.

In 1936, there were about 25 or 30 dairies within a two-mile radius of

Nederland, and some of them were almost up in town. Others, such as my mother, brothers,

and I, were operating a dairy in a sense, because we milked five Jersey cows at 836

Detroit, bottled milk in quart bottles, and delivered it around town on bicycles. East of

the railroad tracks, Dan Rienstra, Bill Rauwerda, Babe Vanderweg, H. W. Sweeney, Johnny

Alvlalrez, and Nike Ruysenaars ran dairies. South of Nederland, Curtis Streetman, Gerret

Terwey, Lohman Brothers, Joe Almond, and three or four Alvarez brothers (down near the

S-Curve) operated dairies. West and north of Nederland were the dairies of John Streetman,

John Henderson, Emmett Smith, Chris Rauwerda, John Koelemay, Saul Trahan, B. B. Epperson,

Gerret Rauwerda, John Friez, L. Otis Block, and I'm sure there were a half-dozen others

whose names I have forgotten, or in the Beauxart Gardens area, I never knew. In addition,

lots of people living up town in Nederland kept a family milk cow in the back yard or

staked on a vacant lot somewhere, not to mention horses, sheep, goats, or swine, all of

which also had to be dipped. My brother and I used to lead our 6 or 7 heads of livestock

to the Vanderweg vat by daylight--one animal tied in back of the other like a mule

train--because we still had to deliver milk and go to school after we got home. The

stupidity of the situation for my uncle (H. W. Sweeney dairy), though was that he was not

permitted to dip his 70 heads of cattle in the Vanderweg vat, even though his cow pasture

ran all the way from the present-day fresh water canal on the Port Neches boundary to the

location of Highland Park School, only one block from the dipping vat. What is now the

fresh water canal dividing Nederland and Port Neches was then an abandoned rice canal that

crossed Block Road (Ave. H), Lambert Road (now Nall St. or Highway 365), and Kitchen Road,

now Merriman St., a good two miles from the Sweeney Dairy. And every Saturday morning, we

would saddle up and drive the seventy head of livestock to the Kitchen Road vat, which

took all morning to dip the herd.

Just this month (July, 1988) I reminded Dr. Streetman of an incident at

the old Vanderweg dipping vat that he had forgotten about. I had just taken our cattle to

be dipped, one of which was a frisky, young red milk cow with her first calf. This cow had

just been dipped and was running loose in the main cow pen there, flicking her ears and

flanks to rid herself of the excess water. The dip solution stung cattle who had open

sores or stings from insect bites, etc. Suddenly some one left the gate open, and that red

cow broke into a lope with intent to escape through it if she could. But as luck would

have it, Ed Streetman, who hadn't yet left for the School of Veterinary Medicine at Texas

A and M, had a roping loop in a lasso so new that it was still stiff, and as that cow

passed by him, about 30 feet distant, Ed swung that rope into the air. The loop settled

down over that cow's horns as beautifully as in any western movie. The cow was moving so

fast that she dragged Streetman about 20 feet, but he finally stopped her by digging in

and plowing up the ground with his boot heels, and never once did he turn loose of her.

After that, I had no further trouble leading the cow back to our barn.

Another event at home could only have happened in Nederland's dairying

days. Like a few other boys in school who grew up in dairying families, my brother Otis

left the cow pen and went straight to school, wearing the same overalls. One day, the

music teacher, a Miss Sigler, caught Otis doing something, throwing spit balls, I suppose,

and she chose to call him up to her desk and warm his britches. Now, Miss Sigler was a

very small woman, and her paddle was as long as she was tall. She made Otis lean over her

desk, with hands outstretched, and she drew that paddle back about six yards and walloped

him good on the seat. Now one of the main ingredients of the cow feed we mixed at home was

cotton seed meal, which was much finer ground than any wheat flour, and it had a way of

getting into clothes worn in the dairy barn and especially into overall pockets. Now when

that paddle struck those overall pockets, the cotton seed meal rose in such a cloud as to

do justice to a Texas cyclone skimming along the ground. At first, Miss Sigler began to

cough and hack, then she began to cry, and finally she just sat down, put her hands and

face down on her desk, and began to "bawl." And Otis, tired of waiting for the

rest of his paddling, finally went back to his seat.

There were a few more early Nederland business houses I want to mention

before I forget about them completely. Around 1952, a man named Joe Bean from Jasper

remodeled a building at 22nd St. and Nederland Avenue, and he founded a grocery called

Nederland Minimax in it. Bean later chartered a corporation capitalized at $1,000,000;

bought about 18 acres of land across from the present-day Hughes Market Basket, with the

intention of building Nederland's first shopping center there. However, he only got three

stores completed before he apparently ran into financial woes. He moved the Minimax store

to the largest of them, after which he leased the other two stores to TGY and Sommers Drug

Co. of Beaumont. Bean later sold Minimax to a Groves merchant who soon changed the name to

Spiers Discount Center. Spiers operated the store for many years, perhaps as many as

fifteen, but he finally closed it up, apparently unable to cope with the new Hughes Market

Basket across the street. The TGY store stayed open ten years, but only because it had

signed a long-term lease it couldn't break. The Somers Drug Store closed up after a few

years.

Joe Spiers went broke in Nederland twice at locations where other

people had profited handsomely. About 1934, a man named C. J. Alegre opened a store in a

small wooden building across from the Doornbos office and the Langham school. During the

depression and war years, Alegre, being a first-rate merchandiser, made a wash tub full of

money in that location, although he did not have any other competition in the north end of

Nederland. About 1948, he enlarged his business by building a new store building, also

across from Langham (that in recent years has most often housed a dancing studio). About

1952, Alegre's health began to fail, and he sold out to Spiers, who promptly "went

bust" on the same spot where Alegre had made a killing. I never did understand why

Spiers came back to Nederland for a second helping of failure, especially since he had

proven himself to be a quite capable and prosperous merchant in Groves.

I would certainly be historically remiss if I failed to mention more

about the Lohman Brothers dairy, located at South 23rd St. and Avenue H, which in 1935 was

the dairying showplace of Nederland. There was one company house on Avenue H (then known

as Wagner Road), in which A. P. Soape, the plant manager, lived. In back of the house were

the huge dairying barns, dry sheds, hay barns, and utility buildings. In 1935, there was

not much of anything else in that area of Avenue H. Everything from the present-day Riley

Funeral Home to 27th Street, and from Ave. H (Wagner Road was then a shelled road) to

Highway 365 was vacant property, consisting only of Lohman Dairy and the Gerret Terwey

dairy barns and cow pastures. As late as 1950, the entire acreage in front of Pat Riley's,

between Sou. 13th and Sou. 16th Streets, was vacant and belonged to Dick Rienstra. On the

west side of the Gulf States Utilities right-of-way, another 25 acres between present-day

South 15th and South 18th Streets was Curtis Streetman's dairy and cow pasture. Along most

of the north side of Avenue H, there was a fenced-in, abandoned rice canal from the

1900-1915 era, that eventually had to have its levees leveled and its canal filled in

before the land could be sold as city lots. This same abandoned canal right-of-way ran all

the way across Nederland, with South 17th, 16th 15th, 14 1/2, 14th, 13th and South 12th

Streets deadended against the canal fence. It also crossed under Twin City Highway and the

railroad tracks, and the deep ditch that currently is in front of the Highland Park School

was once a part of that abandoned canal. The canal crossed Nederland Avenue, near 5th St.,

through a large concrete duct that had concrete guard rails on each side of the road. The

reason that Gage Street is an angled street is because, when J. M. Staffen Addition was

surveyed, the abandoned rice canal right-of-way was the west boundary of the addition, and

Gage Street had to be surveyed up against that canal, which emptied into another abandoned

canal running along Highway 366. Eventually, the levees near Gage Street also had to be

leveled and the canal filled in before the land could be sold as city lots. But now, back

to the history of Lohman's Dairy.

The Lohman Brothers cattle outlay was principally an experimental dairy

that utilized a large herd of about 130 heads of registered Guernsey milk stock--as

beautiful a herd of milk cows as man every applied eyeballs to. For years, the Lohman

Brothers of Port Arthur (who also owned the Home Laundry and an experimental ranch at

Winnie) had been experimenting with prolonged inbreeding, far beyond what any other

dairyman would consider expedient, and in so doing, they developed a herd of about 70

cows, each of whom averaged from 11 to 13 gallons of milk daily. These cows had to be

milked three times a day, and their utters grew so large that some of them had to wear

"cattle brassieres" -- burlap sacks that held them up via leather straps over

the backs of the cows. But despite their beauty as milk animals and their exceptional milk

production, the inbreeding was adjudged a failure because the animals had much less

natural defenses against disease, etc. The lights stayed on all night in the Lohman milk

barns for milking and feeding. These cattle were never allowed out into a cow pasture or

outside a building because even a light rain often made them sick with distemper type

infections. They stayed in their stalls day and night much like the cattle on exhibit in

October at the Beaumont Fair Ground, and they were fed, watered and milked in their

stalls. Because of the experimentation, the dairy kept close record of the herds, milk was

weighed and recorded, tested, feed was weighed and recorded, etc. The Lohmans had another

herd that were not inbred, and these cattle stayed in the cow pasture except at milking

time. And of course, the statistics of one herd were weighed against the statistics of the

other. The dairy produced up to 500 gallons of milk daily, all of which was wholesaled to

Townsends and Dailey's Dairies in Port Arthur, because the Lohmans were not interested in

the retail end of dairying.

About 1940, the Lohmans tired of the dairy business, and they sold out

to S. E. Walling Jersey Farm of Groves, who was a retail dairyman. The first thing that

Walling did was get rid of the Guernsey herds, and put in a bottling system, for Walling

was a milk wholesaler to stores but he had no retail routes to houses. Walling bottled in

gallon bottles at first, and later in gallon and half-gallon paper cartons, but I can't

seem to recall Walling milk ever being sold in quart bottles. Walling milk soon became the

industry standard throughout Midcounty and in much of Beaumont and Port Arthur as well.

About 1952, Walling built a complete new milk plant on Peek Road, then a shelled road, but

soon to become Highway 365, and his was the first brick building, or for that matter, any

business building along that road, now so heavily built up and traveled. But about the

same time Mr. Walling died. His wife, Mrs. Selma Walling, continued to run the business

for a few years, but soon sold out to her new plant manager, who had also been Mr.

Walling's bookkeeper. Walling had always kept a small herd of Jersey dairy cattle, but

these were mostly for looks only, as the dairy produced little milk of its own. Instead,

the dairy sent a stainless steel, 12,000-gallon refrigerator truck through Hardin, Tyler,

Jasper, and Orange Counties each night and bought up the milk production of numerous

dairies. About 1965, the new owner, who still operated under Walling's name, sold out to

the Carnation Company of Houston, who continued for a couple of years to market Walling

milk under that trademark, but they finally shut down the ultra modern Walling plant and

marketed only Carnation products from the Houston plant. About 1968, J. C. Barnes of

Gardner's Grocery told me that Carnation's driver was coming to his store only once

weekly, and he was getting a lot of complaints about soured Carnation products. About

1968, Barnes finally told Carnation to remove all of their products from his store, and

today I don't think that Carnation markets anywhere east of Houston anymore.

About 1942, F. A. Roach leased the lunch counter and fountain in

Nederland Pharmacy to Tom Lee, Sr., who had formerly been a bread truck driver, and his

son, Skeeter Lee. The Lees also profited in that location as there was then no first class

restaurant in Nederland where beer was not also sold, a practice which many church members

objected to. When the Hammock building was completed in the 1400 block of Nederland Avenue

about 1949, the Lees followed Drs. Moore and Hall to Nederland Ave. and founded the Tom

and Skeeter Cafeteria. Tom Lee, Sr., died soon after, but Tom and Skeeter's remained a

popular eating place throughout the 1950's and into the 1960's. However, the cafeteria

closed up about 1966, having apparently lost most of its business to the new fast food

places that were then opening along Nederland Avenue.

Pitre's Cafe is another example of a once profitable business that

"went bust" as soon as it was sold. About 1952, J. E. Pitre sold out and

retired, but within two years, the new owner hung himself to a tree on the outskirts of

Port Neches, apparently suffering financial woes as well. Dick Rienstra was one of those

who went looking for him on Sarah Jane Road after dark, and he flashed his flash light on

two legs dangling from a tree limb in front of him. Mr. and Mrs. E. G. Deese then opened a

drive-in grocery in the remodeled cafe building which they operated for about ten or

twelve years. About 1970, the corner was sold to Mobil Oil Co., who then built the

present-day Mobil station on that corner.

In 1935, there was a two-story, brick building on the northwest corner

of Helena and Twin City (the foundation of which is still there), and the bottom floor was

a combination service station and small grocery operated lby L. B. Cobb. About 1940, Kelly

Whitley, also a former bread truck driver, bought the business and operated it during

World War II. About 1945, he built a new brick, Pure Oil service station on the site of

the former Bartels Bakery at Chicago and Twin City, and being an astute business man as

well, he too profited quite modestly until his death about 1958. But his successors on

that corner failed and eventually closed. In more modern times, that site has been turned

into a plant nursery and florist.

I remember too the Halloweens of the 1930's, when teenage boys, I

suppose, were expected to engage in as much devilment as possible, that is, short of the

jail house. And a dozen paper boys gathering at 2:00 A. M. each morning were not immune

from such devilment, at least for what few moments they could spare away from their paper

routes. But I will say, at least in 1936-1937, they were not guilty of many of the things